Exploring Alterity, Developing Empathy

by Andrea Lerda

Presented at the Museo Nazionale della Montagna in Turin, the exhibition Ecophilia follows intends to explore new forms of relationships with otherness and the need to develop a feeling of empathy with nature.

Conceived towards the end of 2019 as one of the current opportunities that attempt to construe useful visions for “writing a new world” (to quote the words of the anthropologist Matteo Meschiari (1)), the project emerged in a historic moment that not only interacted with the theme tackled by the exhibition but also became a meaningful experience of it.

Ecophilia, exhibition view at Museomontagna, Turin 2021

If we look at what has happened since the Covid-19 pandemic hit our human world, we can see that the debate about coexistence has shifted from a strictly theoretical to a more experiential level.

The enforced lockdowns that obliged millions of people all over the world to isolate themselves inside their own homes generated, conversely, a strong need for open places and natural spaces. The scenes of crowds of people assaulting the mountains as reported by the media should not be understood only as a manifestation of the need to pass time in aesthetically beautiful, relaxing and wide-open places, or the opportunity to walk and breathe less polluted air than in our cities, but, rather, as a natural and inherent call to immerse ourselves in nature and physically and mentally reconnect with energies, sensations and places whose positive effects have repercussions on our physical and emotional well-being. This is the very profound umbilical cord that binds us to the living and non-living world in which we find ourselves and from which, historically, we have evolved.

Unfortunately, we no longer have any awareness of this cord and its powerful vital fluids would seem to have dispersed, drained by the Futurist desire (2) to create a new nature at the service of modernity, annihilating habitats and biodiversities, stories and narrations, and with them lives and vital forces, forms and colours, smells and perfumes.

Already in 1898 John Muir, one of the most influential naturalists in America, engaged in the protection and safeguarding of wild places, wrote: “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilised people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life [my italics].” (3).

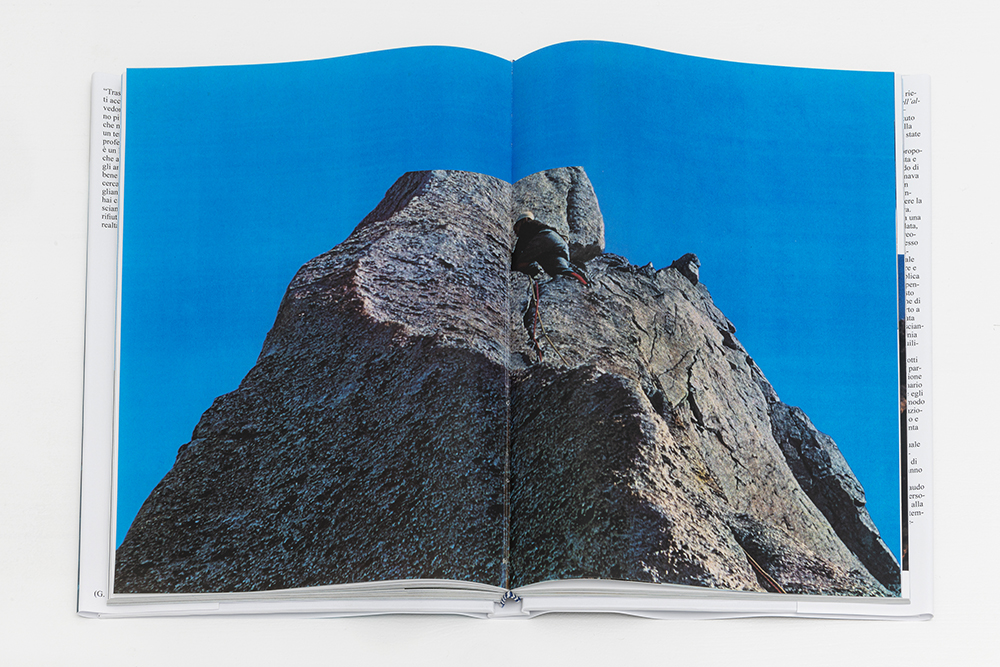

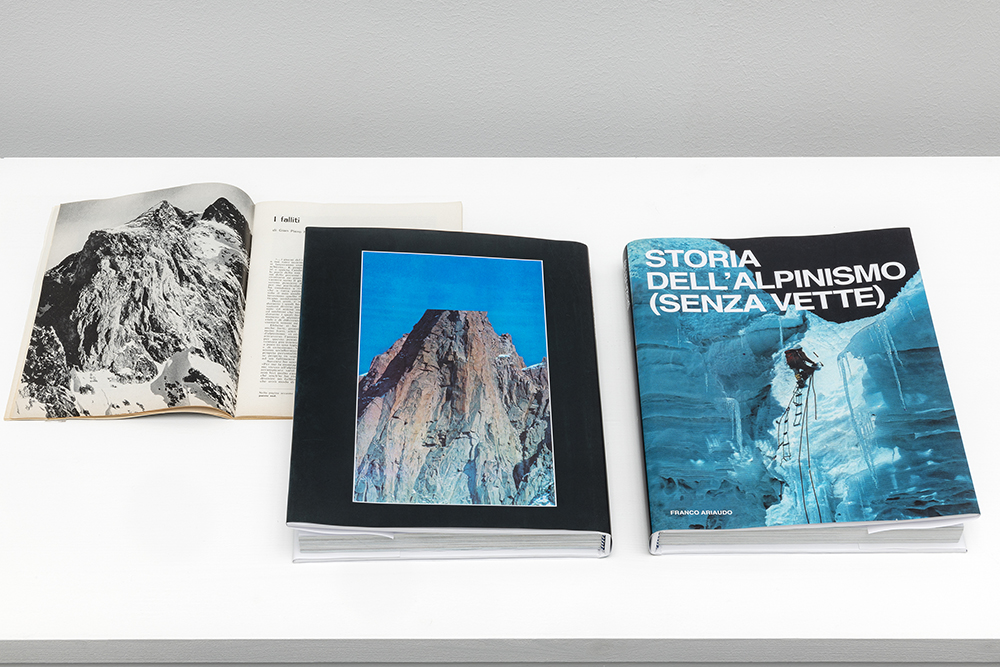

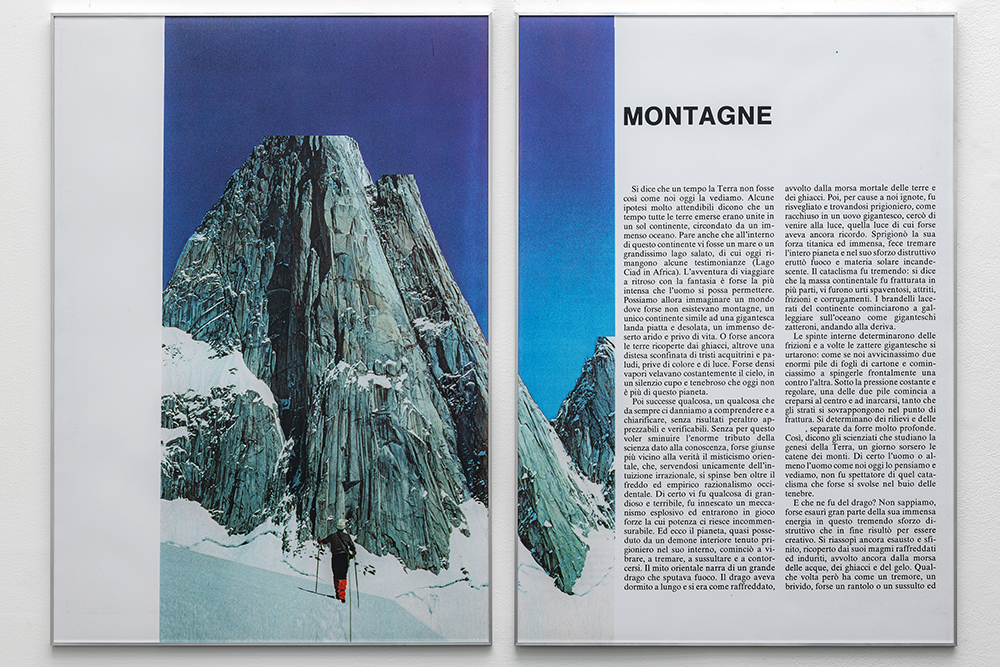

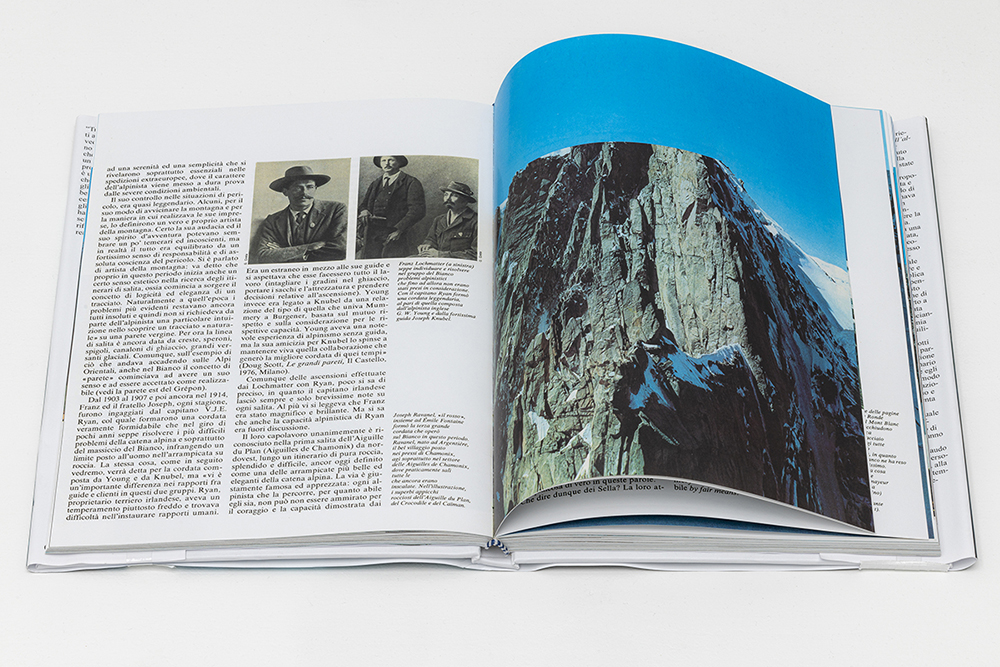

Franco Ariaudo, Storia dell’alpinismo senza vette, 2021. Artist’s book in an edition of 20, 22.5x30 cm. Poster, 70x100 cm

But the world we have created and the post-humanist perspective that resulted have produced new perceptive, emotional and sensorial palimpsests, shifting our ego from its natural ability, as well as need, to empathise with the cosmos in which we are immersed.

So that, over time, faced with the human dilemma of the machine in the garden(4), the knowledge of indigenous peoples and their ability to symbiotically relate to the forests, the countrypersons’ ability to read the vital cycles of the earth and the mountain dwellers’ ability to look after the mountains have all been lost. In a hyper-connected world we are emotionally and synaesthetically disconnected from ourselves and from everything whether known or unknown around us.

Not by chance, in 2003 Glenn Albrecht, an environmental philosopher from Australia, coined the term “solastalgia” – a combination of the Latin word solacium (comfort) and the Greek root algia (pain) – correlating “land health” with “human health” and the loss of environmental integrity with a progressive worsening of mankind’s “psychic stability”.

In the Anthropocene era, devastated by global warming, climate emergencies and extreme meteorological events, solastalgia is thus “the pain or sickness caused by the loss or lack of solace and the sense of isolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory”. (5)

Albrecht sustains the existence of a biological and emotional connection that, on an ontological and genetic level, binds the human being to the world. At the same time, he demonstrates that the empathic relationship with nature is susceptible to change and updating due to the evolutive process and to new social, cultural and environmental conditions within which mankind is prompted to live.

Solastalgia is an emotional state that emerges as a result of human interference in the physical and biological dynamics of Nature. It bears witness to the fact that the anthropic impact on planet Earth, in producing damage to the environment, has repercussions on a physical level (for example, the deforestation to the detriment of the Aboriginal people causes the disappearance of animal and vegetable species; extreme events cause the death of people and, in the destruction of entire mountain valleys – think of the recent devastation of the Roya Valley linking Italy and France – have enormous repercussions on people’s daily life and movements) but above all on an emotional level (creating situations of hardship, illness, stress, anxiety and depression).

All this is proof of our ontological sister and brotherhood with the multitude of places, things and living beings that surround us.

The exhibition Ecophilia reflects on this feeling of physical and emotional connection between the human species and the environment, and on the concept of empathy which, on a genetic and cultural level, links us to whatever around us is comprehensible and incomprehensible. It also focuses on the need to ponder the urgency of a linguistic, cultural and emotional revolution as an indispensable weapon for tackling current challenges and as an extraordinary opportunity for updating our paradigms and our vision of things.

Franco Ariaudo, Storia dell’alpinismo senza vette, 2021. Artist’s book in an edition of 20, 22.5x30 cm. Poster, 70x100 cm

Ecophilia, installation view at Museomontagna

Alongside essential actions on a political and economic level, it is necessary to follow another strategy focussed on bringing into play new educational models, cultural images and visions that – by acting on mental and behavioural mechanisms – succeed in developing a collective feeling of empathy, or ecophilia, with the world, both in the younger and therefore more sensitive swathes of the population, destined to be tomorrow’s society, and in adults.

In this sense, Ruyu Hung, Professor of Philosophy of Education at the Department of Education of the National Chiayi University of Taiwan, uses the term “ecopedagogy”, thoroughly discussed in his essay entitled “Towards Ecopedagogy: An Education Embracing Ecophilia”.

But let us take a step backwards. What do we mean by empathy? How can it represent a means capable of re-establishing an emotional bond with Nature? Why talk of ecophilia in relation to mountains?

In his 1984 book Biophilia, the American biologist Edward O. Wilson uses this term to describe the “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes” (p. 1).

On 12 March 1961, Wilson ventured into the forest of Suriname, near the Arawak village of Bernhardsdorp. In what he himself called a “naturalist’s trance”, the biologist entered a state of “semi-unconsciousness” thanks to which he was able to grasp the complexity and vitality of the “biological maelstrom” he found himself in.

“In a twist my mind came free and I was aware of the hard workings of the natural world beyond the periphery of the ordinary attention, where passions lose their meaning and history is in another dimension, without people, and great events pass without record or judgment. I was a transient of no consequence in this familiar yet deeply alien world that I had come to love. [...] The effect was strangely calming. Breathing and heartbeat diminished, concentration intensified. It seemed to me that something extraordinary in the forest was very close to where I stood, moving to the surface and discovery.

I focused on a few centimetres of ground and vegetation. I willed animals to materialize, and they came erratically into view. Metallic-blue mosquitoes floated down from the canopy in search of a bare patch of skin, cockroaches with variegated wings perched butterfly-like on sunlit leaves, black carpenter ants sheathed in recumbent golden hairs filed in haste through moss on a rotting log. I turned my head slightly and all of them vanished. Together they composed only an infinitesimal fraction of the life actually present. The woods were a biological maelstrom of which only the surface could be scanned by the naked eye. Within my circle of vision, millions of unseen organisms died each second.” (6)

Wilson’s account appears to be extremely lucid. His words enclose not only an awareness of the world made up of species in symbiotic relationship among themselves, in which every detail is vitally important, even if unknown to us, but also proof of a Nature that acts beneficially on the human body. This process of exploration (which is experiencing a revival in these years in scientific, artistic and philosophical spheres) is a path that, in the naturalist’s case, can be followed forever. Wilson goes further, theorising that a naturalist’s view is only a specialised product of a biophiliac instinct that is common to all men, which has to be developed to the advantage of an increasing number of people.

Lia Cecchin, OBE, 2021, puzzle, variable number. Environmental dimension

“Humanity is exalted not because we are so far above other living creatures, but because knowing them well elevates the very concept of life.” (7)

As Giuseppe Barbiero writes in the Preface to his book Introduzione alla biofilia. La relazione con la Natura tra genetica e psicologia, for Wilson what drives a naturalist is not the anxiety for knowledge, nor the pursuit for the success of a brilliant academic career. Instead, it is “biophilia”, the love for life or, more precisely, the innate tendency to concentrate one’s attention on forms of life and on everything that recalls them, and in some case to be emotionally affiliated to them.

“What is it exactly that binds us so closely to living things? The biologist will tell you that life is the self-replication of giant molecules from lesser chemical fragments, resulting in the assembly of complex organic structures, the transfer of large amounts of molecular information, ingestion, growth, movement of an outwardly purposeful nature, and the proliferation of closely similar organisms. The poet-in-biologist will add that life is an exceedingly improbable state, metastable, open to other systems, thus ephemeral – and worth any price to keep. Certain organisms have still more to offer because of their special impact on mental development. In 1984, in a book titled Biophilia, I suggested that the urge to affiliate with other forms of life is to some degree innate.” (8)

This sense of affiliation to the natural world, which in Wilson’s case was particularly directed towards the living sphere, was, instead, related to places for the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan.

A climber feels good on feeling his body in contact with the rock, or on reaching a mountain peak. Each of us enjoys looking at a beautiful church, feels beneficial sentiments when contemplating a beautiful landscape or in being in a place to which we are emotionally bound. In this case, Tuan talks of topophilia, “the affective bond between people and place or settings”. (9)

The places that make up our world are not therefore only something that has to do with a determined space, but are rather something to do with memory, with emotions and with desire. Our relationship with places passes through a constant response to the world from our five senses.

As Vittorio Lingiardi, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, writes: “Our relationship with the landscape [and, I would add, with the world we coinhabit] is not exhausted just by looking. It involves the body and sensorial participation; it is charged with affects and memory.” (10)

The concept that unites these two viewpoints, and that the exhibition attempts to explore, is represented by ecophilia, formulated by Ruyu Hung and understood as the feeling of affinity and bonds that the human being feels for Nature in its entirety.

“The concept of ecophilia is inspired by Edward O. Wilson’s notion of ‘biophilia’ and Yi-Fu Tuan’s concept of ‘topophilia’. Biophilia means ‘the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms’ (Wilson, 1993, p. 31), whereas topophilia means ‘the affective bond between people and place or settings’ (Tuan, 1974, p. 4). The prefix ‘eco’ comes from the Greek ‘oikos’, meaning ‘dwelling place, house, and inhabitation’, while ‘philia’ comes from the Greek ‘philia’, meaning ‘affection and loving’, to express ‘the love of dwelling place’ (McIntosh, 1985). ‘Eco’ (oikos) is widely used to express the sphere that all living organisms inhabit today, i.e. the planet or nature. Based on the above, ‘ecophilia’ can be understood as the human affective bond with the surroundings and all living and non-living beings within.” (11)

Ecophilia, installation view at Museomontagna

The ecophilia that Ruyu Hung talks of is a feeling that involves everything that surrounds us and that can be taught and developed by going beyond the traditional educational norms of contemporary society, responsible for having contributed to produce the crisis of feeling in today’s human being.

The educational approach in question, aimed at developing ecophilia, is the previously mentioned ecopedagogy. A tool based on three fundamental actions: “Learning about nature, learning in nature and learning from nature”. (12) This educational strategy focuses attention on “nature-oriented learning and place-oriented learning” (13) and the student’s direct relationship with Nature.

In its apparent simplicity, the proposal embraces an innovative point of view which, if applied on a broader scale, is capable of developing a new pedagogic model, at the basis of the ecophiliac cultural revolution that humanity so needs.

The exhibition Ecophilia explores this complexity of concepts. Aware of the tremendous challenge that we face, it attempts to tackle a number of aspects at the same time.

In the first place, it tries to go beyond the anthropocentric image, proposing a series of works that stimulate a view of mountains and the world via an ecocentric type of feeling. The works by the six invited artists shift the barycentre through which we observe things, triggering a dynamics of de-anthropisation of thought and narrating the relationship between the human species and the outside – whether it be social, animal, vegetable or cosmic – as a moment of encounter that needs to be rethought.

The exhibition welcomes the thinking of Rosi Braidotti and her thesis about the relational capacity of the posthuman subject, which is not “confined within our species, but includes all non-anthropomorphic elements” (14) in relation to living matter that is not disconnected from the rest of organic life, equipped with “intelligent vitality” (15) and “self-organizing capacity”.(16) Such a concept of “intelligent and self-organizing” (17) matter – which post-anthropocentric thought is capable of recognising – is a fundamental passage of ecophilia, where the proposed thesis tries to deconstruct the “unitary subject of Humanism” (18) and emphasise the non-human, the “vital force of Life” (19) that welcomes, shapes and fuels us, which Rosi Braidotti has coded as Zoe.

Ecophilia questions in parallel the no-limits culture that, traditionally, has seen and sees as protagonists not only the dynamics of economic growth on a global level but, more specifically, also mountain culture itself. Indeed, it is known that the desires to conquer and overcome every new limit, supported by the constant advances offered by science, technique and technology (Carlo Crovella talks of the “vice of hyper-technology” (20)), have altered and compromised the ethical, environmental and psycho-emotional equilibriums that are at the basis of man’s coexistence and survival in the habitat in which he finds himself, whether that is a forest, a city or a mountain ridge.

In this sense, the project attempts to write – perhaps provocatively – another story, in which room is left for a less frenetic and more empathic attitude that is open to observe, feel and communicate with the world in a new way; to think in relation to a complexity of multi-species universes; to welcome the possibility of failure, vulnerability and change; to restore the role of the emotions and passions, in order to counter the modern individual’s loss of emotivity that the philosopher Elena Pulcini writes about, condemned to a state of apathy, limitless individualism and endogamic commnitarianism. (21)

Marco Giordano, In Our Midst, 2021, mixed media. Environmental dimension

A spirit that we can rediscover in, among others, the climber and explorer Walter Bonatti and the climber Gian Piero Motti, two extraordinary figures whose ways of thinking fully interprets the empathic nature that the exhibition Ecophilia refers to.

On a creative level, the exhibition juxtaposes works by six artists from Turin, or in some way linked to the Piedmontese capital, that have been produced specifically for the occasion. The research emerged from a multidisciplinary dialogue that, over the course of a year or so, involved philosophers, anthropologists and experts in sustainability and mountain culture.

The works recount nature’s central role, proposing an alternative way for feeling, seeing and understanding mountains and Nature.

The six artists’ considerations, starting out from a non-anthropocentric idea, explore in various ways the concept of empathy, the state/ condition of reciprocal belonging and interdependence between the human and the non-human spheres.

The way in which the works are presented, rather spread out yet communicating among themselves, requires an unusual reading of the exhibition narrative on the part of the spectator.

In the attempt to offer an alternative viewpoint of things, the layout is guided by the notion of blending, thanks to which references to the works create opportunities for connections, for imagining and for shiftings in meaning that give shape to the whole.

Marco Giordano, In Our Midst, 2021, mixed media. Environmental dimension

Franco Ariaudo proposes a re-edition of the book Storia dell’alpinismo by Gian Piero Motti – published in 1977 by the Istituto Geografico De Agostini – in which all the mountains have been de-peaked, or deprived of their summits.

The artist becomes the interpreter of Motti’s ideas, Motti being, as Marco Blatto writes, “one of the first to understand the novelty of the Californian model and to sustain that climbing and the climb, without giving up any great adventures, could be experienced without the ‘traditional’ dictates”. (22) Ariaudo starts out from the ideas proposed in those years by the Turinese mountaineer and author who, when speaking of the philosophy of the high plateaus, affirmed the need and existence for a type of climbing in which the peak played no part, intending a new way of experiencing the mountain and the sporting feat. The artist’s intervention triggers reflection on the concepts of climbing, limits, conquest and on the stereotypes linked to the words “success” and “failure”.

Lia Cecchin represents in a formal way the experience of interaction and coexistence between the human body and natural space, through a series of puzzles – whose subjects range from mountain landscapes to marinescapes – which the artist hangs in the exhibition halls. These objects trigger their broader message following possible damage inflicted by whoever moves around the space and by means of a dynamic that expressly refers to a by now well-known phenomenon, the selfie snapped during exhibitions, which leads to visitors getting their names in the news thanks to the damage caused to the exhibited works. Starting from these involuntary gestures and ensuing sense of guilt, Lia Cecchin’s work moves within the liminal space between the conscious and the unconscious dimensions, reflecting on a cause-effect dynamics caused by human actions. It provocatively invites spectators to observe themselves from an outside position, pondering how one’s lack of attention can have its own effects on the work of art, understood, in this context, as a simulacrum of the natural world in which we are immerged.

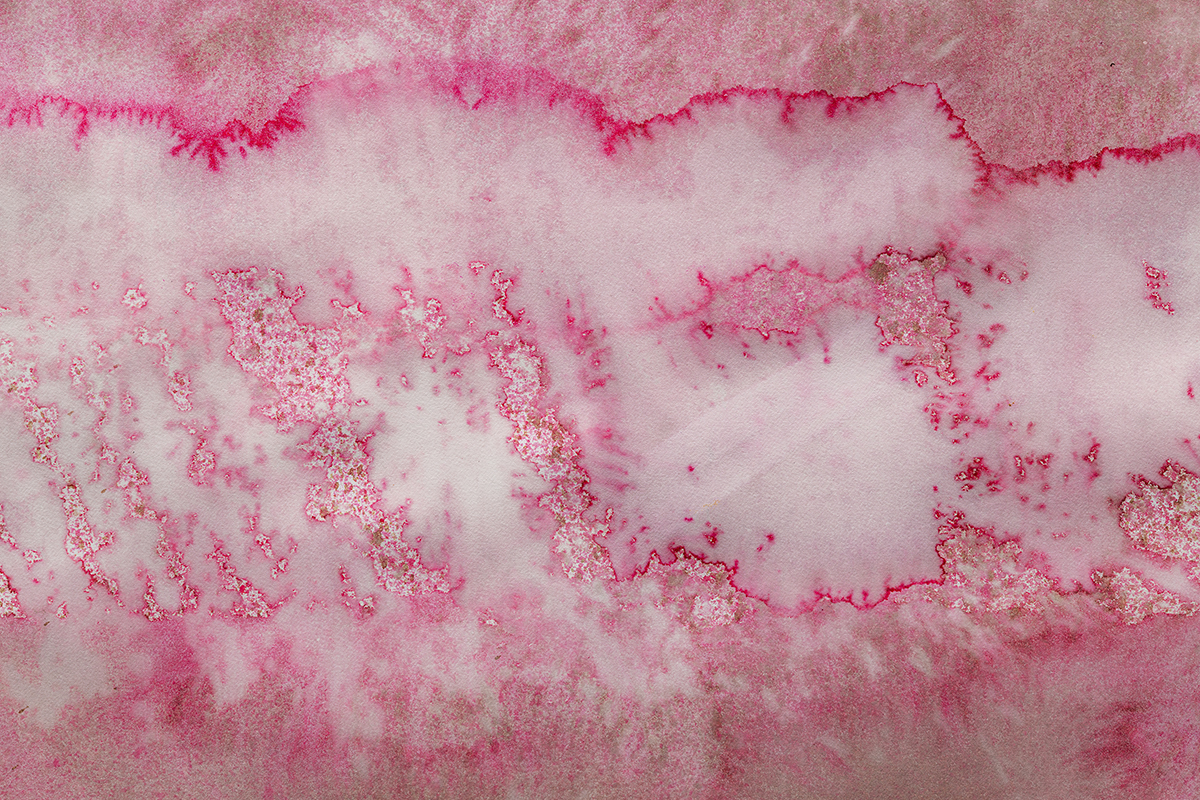

Caterina Morigi, Elitropia, 2021. Paintings: disinfectants on paper. Sculptures: calcium carbonate, disinfectants, polymers. Different dimensions

Caterina Morigi explores the mineral dimension at a micro and macroscopic level as an element of contact between the natural world and the human body. The artist presents a series of drawings and biomorphic sculptures that are part of a process of ongoing research – realised in collaboration with some researchers of the Biology and Orthopaedics Department of the Rizzoli Hospital in Bologna – in which art comes into contact with the field of biomedicine.

At the base of her works realised with biomedical products, disinfectants, antiseptics and biocompatible materials such as calcium carbonate are a series of studies on the possibilities of conserving tomb marble starting out from how human bones function and the use in orthopaedic fields of biocompatible materials produced by marble. As an artistic process of research in progress, Morigi’s work reminds us that the human being is Nature and emphasises how the living and non-living dimensions make up part of the same world of relationships and possible contaminations that can be explored and cultivated with a view to coexistence.

Caterina Morigi, Elitropia, 2021. Paintings: disinfectants on paper. Sculptures: calcium carbonate, disinfectants, polymers. Different dimensions

The works of Marco Giordano and Corinna Gosmaro introduce a series of viewpoints aimed at exploring new ways of intending otherness.

The former presents a series of ceramic flowers, conceived as a sort of spokesperson for the vegetal worlds. After recording the biofeedback of some plants by using electrodes and having transformed these noises into electronic sounds thanks to the use of a synthesiser, Giordano blends these sounds with poetic components that he himself writes and whose narration is entrusted to the voice of a singer. The indecipherable dimension of the traces proposed represent the opportunity for carrying out reflection on the multidimensionality of universal language, on the communicative capacities of plants and on the need to expand our conception of interaction.

Works by the latter artist, instead, focus our gaze on the animal world. Art, in Corinna Gosmaro’s case, is a powerful “practice of de-familiarization” (23) from our mental constructions, in order to effect an exercise of imagining and exploring the liminal space between human and non-human, between known and unknown.

In this way, the ladder made from climbing ropes is not just a presence that alludes to a process of going up and coming down, of evolution or fall, but a figure that, in recalling the shape of a large caterpillar, allows the passage to an imaginative and linguistic dimension lacking in all linear perspective that interests the artist.

Her drawings, which feature a number of birds, introduce a series of interrogatives about birdsong and the possible creative intentions of their chirping and twittering.

Both these artists work on an archetypal level in order to generate a shifting of sense within our sedimented conscious and unconscious narrations, to unhinge the mental scaffolding that defines our concept of alterity, and to generate new imaginative and empathic processes directed towards broadening our sensorial perspectives. Giordano and Gosmaro remind us that not everything can be understood or explained and that our coexistence with other forms of life can take place even without a complete decodification of what is around us.

Corinna Gosmaro, CHUTZPAH!, 2021. Drawings: mixed media, 50x70 cm. Sculptures: technical rope and metal brushes, variable dimensions

Finally Cleo Fariselli proposes an image of such cosmic connection that it appears to be the maximum point of representation of the concept of ecophilia within this exhibition experience.

In the video made by the artist, it seems as though nothing happens. A partially snow-covered mountain landscape blends into an extremely clear daytime sky. However, on the horizon line separating land and sky, a sparkling element attracts the observer’s attention.

Wearing a mirror-dress that reflects the sunlight, the artist dances with the intention of being a star. Fariselli achieves her chameleon-like gesture through which the human figure, harmoniously camouflaged with the cosmos and completely other than itself, is charged with a new positive image, whose brilliance becomes a synonym of light, energy and vital strength.

Broadening the viewpoint from the artistic to the social plane, Ecophilia lays the bases for observing mountains as a preferential place for the ecopedagogy theorised by Ruyu Hung and for a renewal of educational models.

As land at the centre of contemporary environmental exigencies, the mountains of the future do not position themselves solely as an observatory on the front line for analysing the climate changes in progress but also as a preferential laboratory within which a new relationship with the world can be explored.

Mountains and metropolitan-mountain lands, by extension in terms of geographic surfaces and for environmental features regarding natural resources, propose themselves to be preferential future destinations where one can flee from global warming, and where one can live experiences of reconnection with both one’s own and the collective ego and where the healing power of emotions and passions can be rediscovered, along with the healing relationship with Nature, indispensable vehicles for constructing ecophilia and for “looking after the world”. (24)

Cleo Fariselli, Me as a Star (Vallée Etroite), 2021. Video performance. Length: 16’52”

“Let children walk with Nature, let them see the beautiful blendings and communions of death and life, their joyous inseparable unity, as taught in woods and meadows, plains and mountains and streams of our blessed star, and they will learn that death is stingless indeed, and as beautiful as life, and that the grave has no victory, for it never fights. All is divine harmony.” (25)

John Muir’s call to arms is our call to arms to rediscover and train our feeling of “empathic accord” (26) with the world; to political, social and cultural revolution – the new ethico-political articulation that Félix Guattari calls “ecosophy” (27) – and the conversion of an anthropocentric to an ecocentric way of thinking. It is a call to arms to “ecophilia”.

The exhibition Ecophilia originated thanks to intense dialogue with the artists and by means of an indispensable confrontation with a series of important interlocutors who, in various ways, have contributed to the exploration of this concept.

Huge thanks must go to Cala Cimenti (Carlalberto Cimenti), sportsman, alpinist and climber; Paolo Cresci, associate director, head of the sustainability and plants sector at Arup in Milan; Serenella Iovino, Ordinary Professor of Italian Studies & Environmental Humanities, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Federico Luisetti, Professor of Italian Culture and Society at the University of St. Gallen; Roberto Mantovani, author and historian of mountaineering; Fiore Longo, anthropologist and researcher with Survival International, the global movement for indigenous peoples; Angelo Ponta, journalist and author; and Elena Pulcini, Ordinary Professor of Social Philosophy at the Università degli Studi of Florence.

The videos pertaining to talks among the artists, the curator and the people mentioned above are published on the Museomontagna’s YouTube channel.

Ecophilia kicks off the next research path about the relationship between mountains and human beings in the Anthropocene era and is particularly interested in exploring the biological and psychological relationship in the healing process that mountains and the natural world can exercise on man.

With the occasion of Ecophilia, the Museomontagna continues its dialogue with manufacturers attentive to sustainability, and with its own commitment to adopt layout solutions of low environmental impact. For this project, the Museum could count on sponsorship from three important companies. Thanks to its partnership with Aquafil, the exhibition space is covered by carpeting made by ege carpets in ECONYL®, a nylon fibre derived from the regeneration of waste matter recovered from all over the world. The ECONYL® regeneration process in fact transforms what used to be rubbish into a yarn that can be regenerated endlessly, conserving the same characteristics of nylon, the original raw material.

The brand Essent’ial is present in Ecophilia with a series of Eco-poufs made in washable cellulose fibre. Since 2006, the company has shown itself to be one of the Italian brands most attentive to experimenting with eco-sustainable materials and the use of recycled or recyclable materials.

Ecophilia proceeded also thanks to collaboration with the L’Oréal factory of Settimo Torinese. For long engaged in the reduction of CO2 emissions, in the environmental impact of its own industrial production and in the use of renewable energy, L’Oréal Group is reinforcing its commitment in the sphere of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development through its programme “L’Oréal for the Future” for a further transformation of its vision, its objectives and the company onus to face up to global challenges.

ECOPHILIA

Exploring Otherness, Developing Empathy

Franco Ariaudo, Lia Cecchin, Cleo Fariselli, Marco Giordano, Corinna Gosmaro, Caterina Morigi

Curated by Andrea Lerda

Museo Nazionale della Montagna “Duca degli Abruzzi” – CAI Torino

9 June 2021 – 23 January 2022

Notes

1 M. Meschiari, Antropocene Fantastico. Scrivere un altro mondo, Armillaria, Rome, 2020.

2 “We affirm that we can create nature by interpreting its countless apparitions, even through the mathematical, geometrical transformations that modern man imprints on it! To believe that nature exists where there’s disorder, discomfort, chaos (the ‘natural’ as bucolic souls say), and especially where the hand of man is absent, is a pitiful error. We Futurists detest the rural, the peacefulness of the woods, the babbling of the brook... as others say. We prefer men overwhelmed by passion or by the madness of genius; large, popular housing complexes; metallic noises; the roar of the masses”, in U. Boccioni, Futurist Painting Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism), trans. R. S. Agin and M. E. Versari, Getty Publications, Los Angeles, 2016, p. 63. (Original title: U. Boccioni, Pittura Scultura Futuriste. Dinamismo Plastico, Vallechi, Florence, 1977, pp. 11–12.)

3 J. Muir, “The Wild Parks and Forest Reservations of the West”, The Atlantic Monthly, 81:483, January 1898.

4 L. Marx, The Machine in the Garden. Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, Oxford University Press, 1964. With regard to the dilemma that the historian Leo Marx defined as the machine in the garden, Edward O. Wilson wrote: “The Natural world is the refuge of the spirit, remote, static, richer even than the human imagination. But we cannot exist in this paradise without the machine that tears it apart. We are killing the thing we love, our Eden, progenitrix, and sibyl”, in E. O. Wilson, Biophilia, Harvard University Press, 1984, pp. 11–12.

5 G. Albrecht, “Solastalgia. A New Concept in Health and Identity”, in Australasian Psychiatry, February 2007, p. 45: “Solastalgia, in contrast to the dislocated spatial and temporal dimensions of nostalgia, relates to a different set of circumstances. It is the pain experienced when there is recognition that the place where one resides and that one loves is under immediate assault (physical desolation). It is manifest in an attack on one’s sense of place, in the erosion of the sense of belonging (identity) to a particular place and a feeling of distress (psychological desolation) about its transformation. It is an intense desire for the place where one is a resident to be maintained in a state that continues to give comfort or solace. Solastalgia is not about looking back to some golden past, nor is it about seeking another place as ‘home’. It is the ‘lived experience’ of the loss of the present as manifest in a feeling of dislocation; of being undermined by forces that destroy the potential for solace to be derived from the present. In short, solastalgia is a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at ‘home’.”

6 E. O. Wilson, Biophilia op. cit., p. 7.

7 Ibid., p. 22.

8 E. O. Wilson, In Search of Nature, Island Press, Washington DC, 1996, p. 7.

9 R. Hung, “Towards Ecopedagogy: An Education Embracing Ecophilia”, Educational Studies in Japan: International Yearbook, No. 11, March 2018, p. 45.

10 V. Lingiardi, Mindscapes. Psiche nel paesaggio, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milan, 2017, p. 17.

11 R. Hung, “Towards Ecopedagogy...” op. cit., p. 45.

12 Ibid., p. 53.

13 Ibid., p. 52.

14 R. Braidotti, The Posthuman, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2013, p. 60.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid., p. 26.

19 Ibid., p. 60.

20 C. Crovella, Ipertecnologismo – 1 (nella pratica), published on the website OSSERVATORIO sulla Libertà in Montagna, of A. Gogna, available at: http://osservatorioliberta.it/ipertecnologismo-1-nella-pratica/.

21 E. Pulcini, La cura del mondo. Paura e responsabilità nell’età globale, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin, 2009.

22 M. Blatto, “La libera avventura esplorativa di Giancarlo Grassi”, June 2018.

23 R. Braidotti, The Posthuman op. cit., p. 167.

24 E. Pulcini, La cura del mondo op. cit.

25 J. Muir, A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston-New York, 1916, chapter 4.

26 P. Gilardi, “Intervista a Piero Gilardi”, in Compost. Riflessioni sull’ecocentrismo, Kabul Magazine, Turin, 2017, p. 34.

27 F. Guattari, The Three Ecologies, The Athlone Press, London-New York, 2000, p. 28. (Original title: Les trois écologies, Edition Galilée, Paris, 1989.)